|

|

Islands of Hope is

a multi-format social justice project presenting historical accounts and

compelling family stories to help inform the American public regarding

Puerto Rico and Hawaiʻi and U.S. policies which have greatly impacted

island families since U.S. occupation.

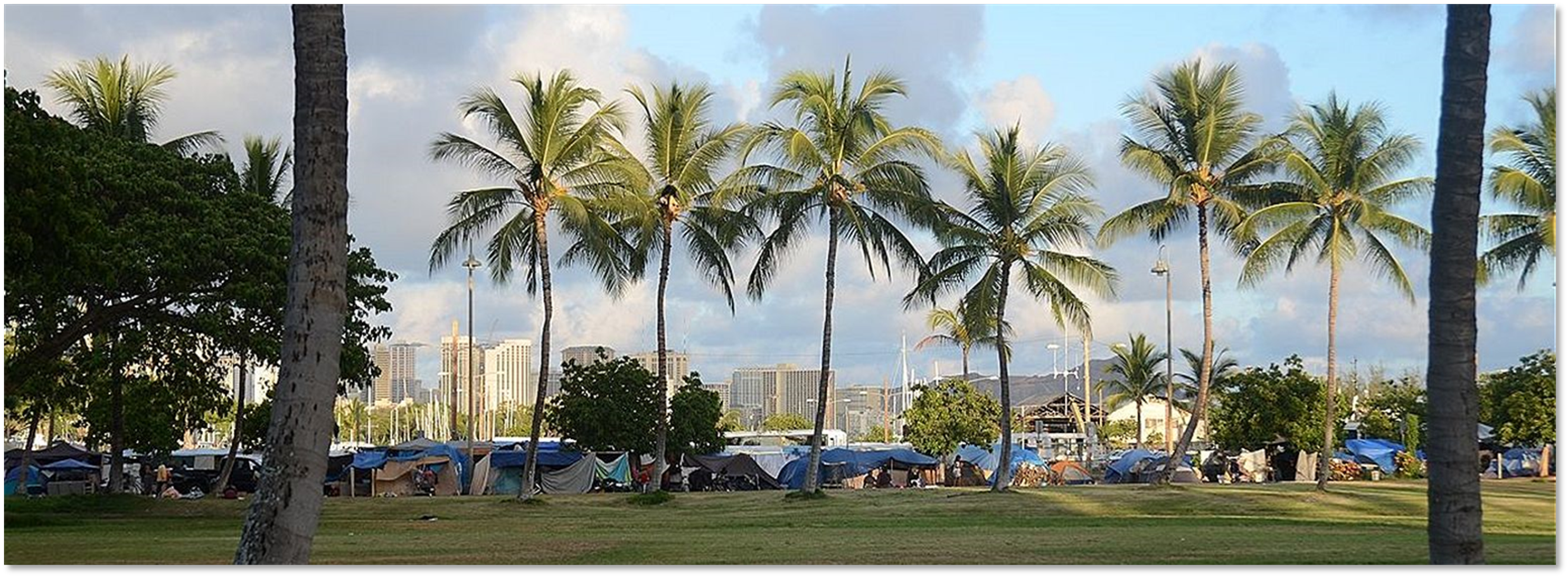

Community Lost

Evicted, extracted, removed. Following

U.S. occupation of Puerto Rico (Borikén) in 1898, U.S. territorial policies

actively removed native Boricua families from their farms, and tore

communities apart, as the land moved into the hands of American banks and

sugar syndicates. Extracted from Borikén, the first of many families

boarded a ship in November 1900, bound for Hawaiʻi to serve as servile

labor on sugar plantations there.

Today, the United States is again

implementing policies that separate children from parents1 and economic

policies, practices, and conditions that push poor and low-income families

into the street, family shelters, or homeless camps.2

1 June 26, 2018, a

federal judge issued an injunction against the Trump administration’s

“zero-tolerance” policy that was separating children from parents at the

border. That same day, the U.S. government was returning the remains of

George Ell to relatives in Montana. Taken from his parents in 1890, the

17-year-old Ell died in Pennsylvania a year later. His parents weren’t

notified for over a year, and requests to return Ell’s remains were

repeatedly denied.

2 Desmond describes

policies, practices, and experiences in Evicted:

Poverty and Profit in the American City.

Islands of Hope

A village of house-less Native Hawaiians,

squatting on state-owned land on the Waiʻanae Coast west of Honolulu

for over 10 years, holds nearly 250 people, including about 50 children.

The camp has developed a self-governing structure, provides support to

resident families, serves as an interface for political, social, and health

agencies—and acts as a collective safety net for the children. Looking for a more permanent sanctuary

for their village, they offer one example of an “island of hope” for a

vulnerable population in paradise.

|

|

֍

January 4, 2016.

It was Monday morning and I was running

late. January 4th was my

first day back to work in Honolulu after the long flight from Seattle and Christmas

and New Year’s spent with family on the continent—or the mainland, as

people inappropriately say. I worked

near downtown Honolulu at the corporate headquarters of Kamehameha Schools

(KS), a private K-12 school system for Native Hawaiians that was endowed in

1883 by Bernice Pauahi Bishop, great-granddaughter of Kamehameha I. As a senior research associate at KS, I

had previously scheduled myself into an all-day session up at the high

school campus.

I thought

about skipping the Hawaiian Leaders session. I didn’t want to walk in late. It would be rude, especially given the

fact that I would likely be the only non-Native Hawaiian in the room and

would be there only as a guest. But

I had been the one who in December had approached William (BJ) Awa, Jr.,

director of the First Nations’ Futures Program (FNFP), to ask permission to

attend the orientation session for the new cohort of FNFP fellows. The speakers would be noted Native

Hawaiian community leaders who would relate their experiences—in business, non-profit,

and professional organizations—to young Native Hawaiian professionals who

had applied, and been selected as fellows, for the tenth FNFP cohort.

I wanted

to attend. I wanted to listen. I wanted to learn. So even though I was late that morning, I

drove to the Kapālama high school campus

overlooking Honolulu. I parked and walked

up the steep flights of concrete steps to the spacious Ka‘iwakīloumoku Hawaiian Cultural Center,

walking casually so as not to be perspiring profusely on that already warm

January morning. My plan was to see

if I could artfully and tactfully slide into the room without disturbing

anyone.

Opened in 2012, the Ka‘iwakīloumoku

Hawaiian Cultural Center had been envisioned as a catalyst for the

revitalization of Hawaiian culture more than two decades earlier by former

Kamehameha Schools trustee Myron “Pinky” Thompson, father of famed

Polynesian voyaging navigator Nainoa

Thompson. During the week of January

4, the Cultural Center was hosting new First Nations’ Futures Program

fellows attending orientation meetings before beginning a year-long

project-based collaboration to study, design, and produce a product or

activity benefitting the Native Hawaiian community. The collaborative effort was intended to

develop leadership skills. Brainchild

of Neil Hannahs, the Kamehameha Schools Land

Assets Director, the project was coordinated with Stanford University, Hannahs’ alma mater, and included parallel cohorts of

Alaska Native fellows and Maori fellows in Aotearoa (New Zealand).

That

January morning, I stopped on the covered walkway at the edge of the

center’s conference hall and listened closely. The grand meeting hall, with its high

ceilings and immense ceiling fans, could be divided into three large rooms

utilizing retractable mobile walls, as was the case this particular

morning. However, like an

amphitheater, the long south-facing wall of the building, along the walkway

and large open grass courtyard overlooking Honolulu and the Pacific Ocean,

often remained open. As I stood on

the walkway, I could hear a single male voice issuing from the far

room. So I

moved down the walkway to the edge of that room and stood behind the

retractable sidewall, listening.

The

speaker was talking in a casual tone of voice. I couldn’t hear any shuffling papers or

movement of people in the room.

After a moment, I poked my head around the corner and surveyed the

room quickly before withdrawing behind the wall again. The tables were positioned in a long

rectangle in the center of the large room.

Standing at the far end was the speaker, Thomas Kaulukukui—Vietnam

veteran, former teacher, retired judge, and current board chair of Lili‘uokalani Trust

established by Queen Lili‘uokalani to care for

orphaned and destitute children.

FNFP fellows and KS staff were seated along the parallel sides and

south end of the table. I noted

empty chairs, but they were tucked between individuals. It would be disruptive to enter and take

a seat, but it would be a larger distraction if I entered and remained

standing against the wall. I weighed

the options: enter and create a

momentary disruption, wait and listen behind the wall until Kaulukukui finishes speaking, or simply turn and take

my leave.

Hawaiians

and their warm aloha spirit never cease to amaze me. I’d barely begun my deliberation before

BJ Awa was standing directly in front of me, indicating I should follow him

into the room. “I don’t want to

interrupt,” I protested quietly. Awa

motioned again and insisted calmly, “Come on.” He pointed to an empty chair on the near

side as he continued across the room and around the table to his seat on

the far side. Kaulukukui

acknowledged me subtly with his eyes but did not break from the story he

was telling. And people around the

table were not the least bit distracted from listening attentively to Kaulukukui.

Warm. Inclusive. Accepting. Aloha.

That is what I remember about that session on January 4. And I remember Thomas Kaulukukui

stating that people who live in Hawai‘i all have

one thing in common, as he saw it.

They were there because someone was a risk-taker. Someone left their home and journeyed to

find a new home in Hawai‘i—the most isolated place

on earth. Each faced challenges. Each

had a story. From ancient Polynesian

voyagers who first sailed the entire Pacific Basin, to European explorers

who entered the Pacific looking for riches in China. From Asian immigrant farm workers looking

for a better life for their families, to North American families looking to

live in a Hawaiian paradise.

Risk-takers all.

Awa stood

and introduced the next speaker, Nālei Akina, administrator at Lunalilo

Home, another social institution and private operating foundation

established by a Hawaiian monarch. Akina opened with an oli, a Hawaiian chant. Then she introduced and identified

herself by describing her family and her teachers—her genealogy, kumu hula (hula teacher), and schooling. A graduate of Punahou (Barack Obama’s

former high school) and Cornell University, Akina

spoke of working for Alvin Ailey Dance Troupe in New York City and the

pleasure she felt upon returning to Hawai‘i. Then she described her work at Lunalilo Home and in other non-profit

organizations. Later, during a break,

I asked her about visiting Lunalilo Home and she

agreed to give me a tour.

William

Charles Lunalilo was the first elected king of Hawai‘i

but only served for just over a year.

In 1874, at the age of 39, he died of tuberculosis. Known as the People’s King, he was a

compassionate and caring leader. It

caused him great pain to witness poverty, homelessness, and disease spread

through the island kingdom after Western contact. So, on the advice of Bernice Pauahi

Bishop and her American banker husband, William Lunalilo

created a will in which he directed his vast landholdings across five

islands be set aside in a trust after his death to establish a residential

care facility for elderly and destitute Hawaiians. Lunalilo

Trust. Lunalilo

Home.

One afternoon,

I visited Lunalilo Home. Nālei Akina showed me through the facility, introducing me to

staff and to the Home’s programs and services. Then we stood outside under a tall

spreading shade tree and she answered questions about the financial situation

Lunalilo Home faced. The once wealthy Trust— endowed with the

largest private landholdings in the Kingdom of Hawai‘i—was

now dependent on gifts and donations.

How could that be, I wanted to know.

There seemed to be little information available about the trust and

its management by Americans who served as the initial trustees of Lunalilo’s estate.

“Very

little’s been written,” Akina responded. She mentioned a children’s book about

William Lunalilo published by Kamehameha Schools

and a master’s thesis about Lunalilo Trust

written by a student at the University of Hawai‘i. Abruptly she stopped, turned to face me

squarely, and stared as if right through me. “You said you’re a researcher and

writer,” she stated. “Why don’t you write about Lunalilo

Trust?”

Islands of Hope began as a look into the ways in which a

wealthy and land-rich trust, established to care for elderly and destitute

Hawaiians in the Kingdom of Hawai‘i in the late 1870s, was drained and depleted by American businessmen

and lawyers who, as appointed trustees of a king’s estate, became wealthy

at the expense of generations of Hawaiians to come. It is seemingly a case of individual and

corrupt self-interest trumping an entrusted responsibility to serve the

greater good of the community, of the nation. That initial “look” into circumstances

surrounding Lunalilo Trust expanded into a

broader examination of patterns in our American history and political

policies—patterns evident in national debates and policymaking today. Further spurred by the raucous political

debates that ensued during the 2016 presidential election campaign, Islands of Hope is an attempt to

illuminate the ongoing struggle between individual, community, and national

interests, values, and ideals.

|